English and Creative Writing at Franklin College

The Franklin College Department of English and Creative Writing is committed to the careful study of the individual expression and cultural values found in English, American, and world literature.

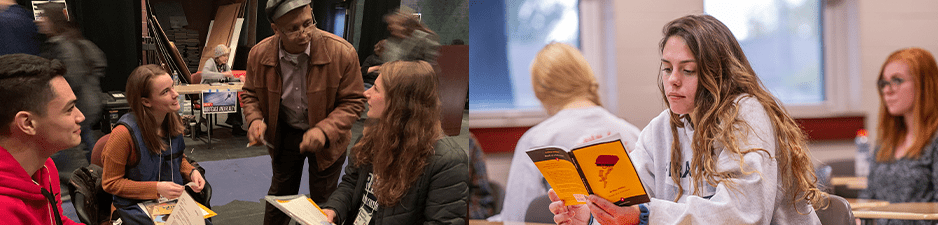

The department is one of Franklin College’s most exciting intellectual communities. Our faculty of dedicated teacher-scholars share with students their expertise in, and enthusiasm for, literature from a variety of genres, periods, and cultures—works drawn from the traditional canon to the works of emerging artists, from Greek tragedy to graphic novels, from Shakespearean sonnets to postmodern poetry. Small class sizes mean professors get to know their students and can engage with them in intense debates and deep analyses of literary works that continue outside the classroom.

Our dedicated faculty of practicing writers and scholars guide students in small classes and workshops that cover a variety of genres, as well as provide students with frequent out-of-class opportunities to exercise and hone their craft. Creative writing students can expect a rigorous yet collegial environment that allows for engaged learning, collaboration and experimentation.

Download the English Major Handout (PDF)

Download the Creative Writing Major Handout (PDF)

Mission

By honing a diverse set of reading and writing skills, the English and creative writing department’s majors and minors recognize the artistic achievements, insights, and possibilities inherent in literature to create their own meaningful work as they prepare for professional positions, graduate study, and civic engagement.

Our Faculty

In addition to their commitment to the classroom, faculty in the English and creative writing department maintain active scholarly agendas, publishing their research and presenting at major national and international conferences on a wide variety of topics, including the intersections of narrative theory and gender theory; the limitations of humanity in Shakespeare’s Richard II; modernist irony as a response to colonial exhibitions; flipped classroom pedagogy; landscape and medieval gender roles; feminist readings of global modernism; and deforestation in contemporary Anglophone Caribbean literature. In addition, our creative writing faculty have won awards and national attention for their work.

Departmental Highlights

Why English at Franklin?

- Dynamic classroom experiences. Franklin College English professors use a variety of approaches that focus on how language and literary forms recreate both individual experiences and the large, impersonal forces that shape cultures and historical periods. In so doing, we seek in our classes to understand the many varieties of the human condition. In addition to taking courses with our award-winning faculty, our creative writing students benefit from the creative writing program’s reading series, which brings talented poets, fiction writers, memoirists, and playwrights to teach and study with them each year.

- Experiences beyond the classroom. Not only do English and creative writing majors learn a great deal in the classroom, they also take part in activities related to the disciplines. Such activities regularly include working on the editorial board of the college literary journal, the Apogee (founded in 1961); attending performances and creative-writing readings; and participating in other events in and around Franklin, Indianapolis, Bloomington, Louisville, and elsewhere in the region.

- Global engagement. With opportunities to study abroad during entire semesters, during the college’s four-week Immersive Term, or over the summer, English majors have recently taken courses in England, France, Spain, Costa Rica, Germany, Uganda, Japan, and elsewhere.

- Interdisciplinary commitment. In keeping with the college’s strong interdisciplinary character, English majors frequently choose to pursue a second major or a minor in disciplines such as creative writing, elementary education, French, history, multimedia journalism, political science, philosophy, psychology, religious studies, or Spanish. Recent English courses have been cross-listed in theatre and the liberal arts program, and students may count an upper-level course in French or Spanish literature toward their English degree.

- Connecting passion with work. Our faculty advisers are committed to helping students find careers in fields that excite them. Recent graduates have used their English degrees to pursue rewarding careers in teaching, publishing, health care, marketing, business, the performing and creative arts, communications, technical writing, and non-profit management. Others have gone on to graduate programs in English, law, divinity, library science, and counseling.

Requirements

Introductory courses provide students with an understanding of different creative genres, as well as the fundamentals of creative writing processes, literary citizenship and the contemporary literary landscape. Students learn to read like writers, engaging in literary analysis to appreciate the nuances of text construction. In later courses, students perform genre-specific studies, closely studying, deploying and sharpening particular writing techniques, and engaging in significant revision and experimentation as they hone their unique voices and join ongoing literary conversations.

As creative writers, we untangle texts and cultural contexts to discover new strategies for reading and writing, with students interrogating both the worlds of the texts they read and write, and their own world, understanding how texts communicate, shape and move all of us. Through guided practice, students gain confidence, empathy, and practical critical writing and thinking skills that allow them to make powerful contributions to the world.

-

“

“The student-teacher ratio, I never realized how important that would be, but it’s super important. I’ve been in classes with five people, and you get to work with the professors themselves. It’s great.” - Sam Fain '20

Meet Our Faculty

Assistant Professor of English and Creative Writing

Katie Burpo, M.F.A.

Phone: 317.738.8147

Email: kburpo@FranklinCollege.edu

Associate Professor of English and Chair of English Department

George Phillips, Ph.D.

Phone: 317.738.8241

Visiting Assistant Professor of English and Creative Writing

Emily Banks, MFA, Ph.D.

Phone: 317.738.8222

Email: ebanks@FranklinCollege.edu

Assistant Professor of English

Anna James, Ph.D.

Phone: 317.738.8411

Email: ajames@FranklinCollege.edu